Why Protecting Instructional Time for “Book Language” Matters

Written by Amelia Larson

Educators, especially those working with multilingual learners, often champion reading as a cornerstone of language development. But beyond simply reading more books, there’s a deeper truth: the kind of language found in books—what researchers call “book language”—is qualitatively different from everyday speech. It’s this unique, sophisticated input that plays a critical role in shaping children’s language, literacy, and cognitive development.

This insight is powerfully supported by studies like:

-

- The Impact of Language Experience on Language and Reading by Seidenberg & MacDonald (2018),

- Book Language and Its Implications for Children’s Language, Literacy, and Development by Nation, Dawson & Hsiao, and

- Differences in Sentence Complexity in the Text of Children’s Picture Books and Child-Directed Speech by Montag et al.

What Is “Book Language”?

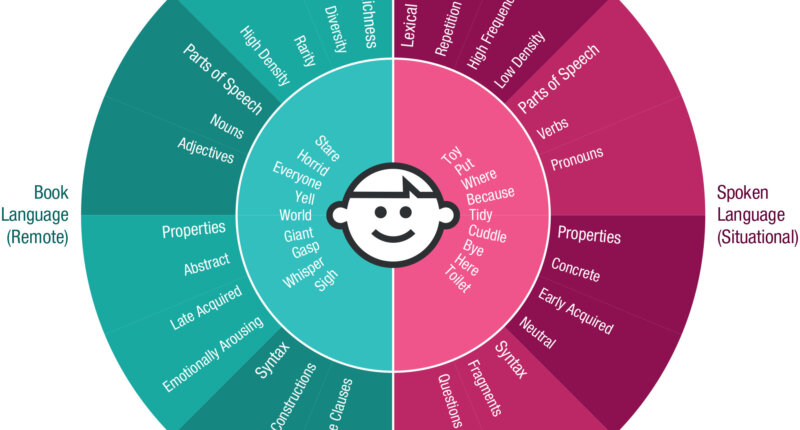

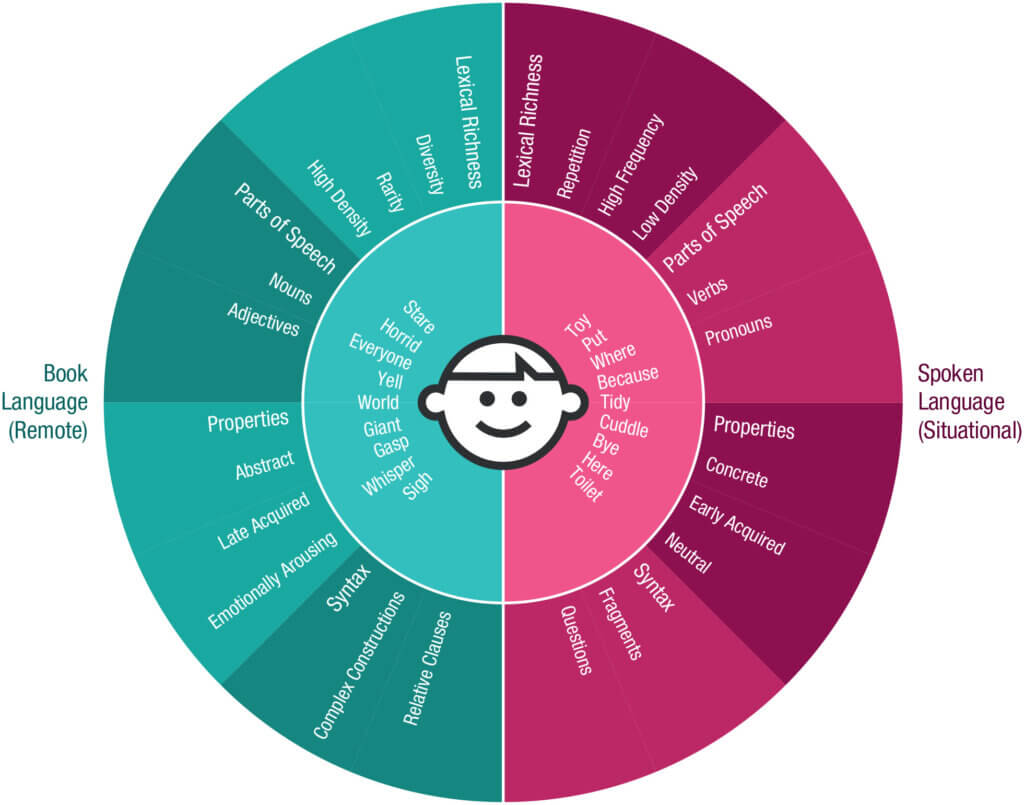

“Book language” refers to the distinct linguistic characteristics of written text—especially children’s literature—that set it apart from conversational speech. Compared to oral language, book language features:

-

- Higher lexical density (more content words per sentence)

- Richer and more diverse vocabulary

- Greater morphological and syntactic complexity

- More abstract and emotionally nuanced expression

Crucially, these features are not just decorative. They have a cumulative impact on language acquisition, reading development, and academic success, especially for multilingual learners.

The Developmental Power of Book Language

Kidd & Donnelly (2018) demonstrated how language experience directly supports reading acquisition, especially through statistical learning—the brain’s ability to detect patterns in language. Exposure to book language builds the foundation for reading success by providing repeated encounters with grammatical patterns, rare words, and advanced sentence structures.

Spoken Language

The benefits of book language extend beyond reading. Children who are regularly exposed to text demonstrate greater capacity to produce grammatically complex speech, even outside of reading contexts. This reinforces the idea that literacy feeds back into oracy.

Social and Emotional Growth

Books often convey emotions and relationships through rich language and nuanced narratives. This exposure fosters empathy, emotional vocabulary, and perspective-taking—vital skills for children, especially those navigating multiple linguistic and cultural identities.

Key insight:

“Children vary enormously in their early language experiences, and these differences strongly influence how readily they learn to read.”

—Seidenberg & Macdonald

Statistical Learning and Book Language: A Perfect Pair

Seidenberg and MacDonald (2018) argue that language experience is central to learning to read, not just phonics or decoding in isolation. Their “statistical learning approach” explains:

-

- How the brain picks up on patterns in language (word order, syntax, morphology) through frequent and meaningful exposure.

- Children who encounter more varied and complex language—especially through reading—develop more robust language representations, which in turn support reading comprehension.

Book language is rich in the very patterns and structures that statistical learning thrives on:

-

- Consistent syntax patterns (e.g., “Although she was tired, she kept reading.”)

- Morphological cues (e.g., “unpredictable,” “kindness,” “miscommunication”)

- High-frequency abstract structures (e.g., passive voice, embedded clauses)

Children who regularly interact with book language internalize these complex patterns, which sharpens their ability to make predictions, decode meaning, and generalize across texts—essential skills for proficient reading.

Multilingual learners often have stronger oral skills than literacy skills in the language of instruction. Intentional exposure to book language helps close this gap by training the brain to notice and learn the statistical patterns unique to written discourse.

Key Linguistic Features of Book Language

1. Lexical Density and Vocabulary Breadth: Books, even those written for preschoolers, introduce more words—and more unique words—than everyday conversation. This increased word exposure helps build deep, durable vocabulary knowledge.

Example:

Spoken: “The bird flew.”

Book: “The majestic falcon soared effortlessly across the crimson sky.”

2. Vocabulary Sophistication: Research by Dawson, Hsiao, and Nation reveals that book vocabulary tends to be:

-

-

-

- Abstract: These words express ideas or concepts not tied to physical objects (e.g., freedom, curiosity)

-

-

“The children’s eyes sparkled with curiosity as they opened the mysterious, dust-covered book.”

-

-

-

- Emotionally Rich: These words evoke strong feelings or emotional responses (e.g., grief, joyous).

-

-

“A joyous cry erupted as the last puzzle piece into place.”

3. Content-Heavy Language (Nouns and Adjectives): Book language is dense with descriptive nouns and adjectives that build conceptual understanding.

“Her backpack contained a magnifying glass, a journal, and a crumpled map—tools for her latest scientific expedition.”

4. Morphological Complexity: Words in books often contain multiple morphemes—roots, prefixes, and suffixes—that signal meaning and grammatical function. This morphological richness supports vocabulary expansion and reading comprehension. Multilingual learners can especially benefit from comparing cognates and affixes across languages to develop cross-linguistic awareness.

“The child’s misunderstanding of the instructions led to a humorous outcome.”

Morphological Breakdown:

-

-

-

-

- mis- (prefix meaning wrong or bad)

- understand (root verb)

- -ing (suffix forming a noun from a verb)

-

-

-

5. Syntax and Sentence Complexity: Two landmark studies underscore the dramatic differences in syntax between book language and spoken language:

Montag, Jones, & Smith (2019) found that the sentence structures in children’s picture books were significantly more complex than those used in child-directed speech.

Kidd & Cameron-Faulkner (2015) in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General demonstrated that text exposure directly predicts children’s and adults’ spoken production of complex sentences. In other words, the more we read, the more syntactically complex our speech becomes.

Example:

Spoken: “He was hungry.”

Book: “Despite having eaten just an hour before, the rumbling in his stomach suggested otherwise.”

Instructional Implications for Multilingual Learners

Multilingual learners (MLs) often straddle two or more language systems. For them, book language can be a bridge—offering exposure to academic English, modeling complex syntax, and expanding content knowledge. Here are a few high-leverage practices

-

- Prioritize read-alouds with complex texts and give multilingual learners time to process and engage with new words. Pre-teaching key vocabulary and using visuals or gestures can make book language more accessible.

- Provide Scaffolded Access to Rich Texts: Don’t simplify texts too much for multilingual learners. Instead, scaffold comprehension (e.g., pre-teaching key vocabulary, using visuals, asking prediction questions) to preserve exposure to book language and promote statistical learning.

- Bridge Oral and Written Language: Often, Multilingual learners often have stronger oral skills than literacy skills in the language of instruction. Intentional exposure to book language helps close this gap by training the brain to notice and learn the statistical patterns unique to written discourse.

- Support Transfer Across Languages: While statistical patterns differ across languages, multilingual learners can transfer conceptual knowledge and awareness of how language works—if educators make those connections explicit. For instance, recognizing that Spanish and English both use noun-adjective structures (but in different orders) support syntax learning.

- Leverage Interactive Read-Alouds Interactive read-alouds, with guided discussion and re-reading, offer a powerful way to immerse students in book language. These interactions can boost syntax processing, vocabulary acquisition, and narrative understanding.

- Explicitly teach language features—highlight new vocabulary, unpack complex sentences, and analyze word structure.

- Pair reading with oral language practice—ask students to retell, paraphrase, or discuss texts using academic language.

- Bridge book language with home language knowledge to support transfer and understanding. Build home-school connections—encourage families to read aloud in any language and talk about stories together.

- Pair Books with Oral Language Activities

Connect book reading to speaking and writing tasks. For example, ask students to retell a story using book-style phrases, or to write using newly acquired vocabulary. This helps solidify statistical patterns across modalities.

Moving Forward:

Literacy development is complex and multifaceted. Exposure to book language provides opportunities to experience words and sentences that are rarely encountered in conversations. These differences are evident in the books children hear in the context of shared reading. Such learning establishes the foundations for more advanced language development as well as literacy.

“Book language” isn’t just a literary luxury—it’s a developmental necessity. It provides the rich, varied, and complex input that students need to thrive as readers, writers, thinkers, and speakers. As Seidenberg and MacDonald remind us, learning to read is learning a new language: the language of print. Time must be protected, prioritized, and practiced—every day. We can’t risk squeezing out the space needed for children to explore syntax, book language, sentence comprehension, passage understanding, and—perhaps most importantly—reading itself.

For multilingual learners, especially, frequent and scaffolded interaction with book language is not just a supplement; it is an essential element in the statistical learning journey that drives language proficiency and reading success.

References and Further Reading

-

- Seidenberg, M. S., & MacDonald, M. C. (2018). The Impact of Language Experience on Language and Reading: A Statistical Learning Approach. Link to article

- Nation, K., Dawson, N. J., & Hsiao, Y. (2020). Book Language and Its Implications for Children’s Language, Literacy, and Development.

- Montag, J. L., Jones, M. N., & Smith, L. B. (2019). Differences in Sentence Complexity in the Text of Children’s Picture Books and Child-Directed Speech.

- Kidd, E., & Cameron-Faulkner, T. (2015). Text Exposure Predicts Spoken Production of Complex Sentences.